BORN: Tokitarō 時太郎 supposedly October 31, 1760

Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan

DIED: May 10, 1849 (aged 88) Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan

Nationality Japanese

Known for Ukiyo-e painting, manga and woodblock printing

Hokusai The complete Works

Hokusai Museum Tokyo

NOTES: Hokusai’s work had already been recognized outside of Japan during his lifetime. For instance, Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), a visiting doctor at a Dutch trading post in Japan, adopted works of Hokusai Manga (“Hokusai Sketchbooks”) into his book “Nippon,” which was published between 1832 and 1851. However, it was only after the onset of Japonism popularity upon the International Exposition of 1867 held in Paris that his name became highly acknowledged. Ukiyo-e was introduced along with a number of artifacts during the world’s fair. The dynamic composition and bright coloring were revolutionary to the European art world causing a major impact towards European artists, and triggering the birth of impressionism.

The influenced artists include Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Edgar Degas (1834-1917). Degas made a figure painting he learned from the Hokusai Sketchbooks. Inspired, Henri Rivière (1864-1951) created a series of lithographs called the “Thirty-Six Views of the Eiffel Tower,” modernising Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.”

Émile Gallé (1846-1904), a famous glass artist of the Art Nouveau movement made a flower vase that adopted designs from the Hokusai Sketchbooks. The composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918) drew inspiration from “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” one of the prints from the “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji” series, for his symphonic poem La Mer.

Hokusai had a profound influence on European artists and continues to gain international acclaim to this day. In 1960, he was honored at the Congress of the World Peace Council in Vienna for his contribution to the promotion of culture worldwide. In 1999, he was the only Japanese person given a place in Life Magazine’s “The 100 Most Important Events and People of the Past 1,000 Years.”

In 1839, a fire destroyed Hokusai's studio and much of his work. By this time, his career was beginning to fade as younger artists such as Andō Hiroshige became increasingly popular. But Hokusai never stopped painting, and completed Ducks in a Stream at the age of 87.

Constantly seeking to produce better work, he apparently exclaimed on his deathbed, "If only Heaven will give me just another ten years ... Just another five more years, then I could become a real painter." He died on May 10, 1849 (18th day of the 4th month of the 2nd year of the Kaei era by the old calendar), and was buried at the Seikyō-ji in Tokyo (Taito Ward).

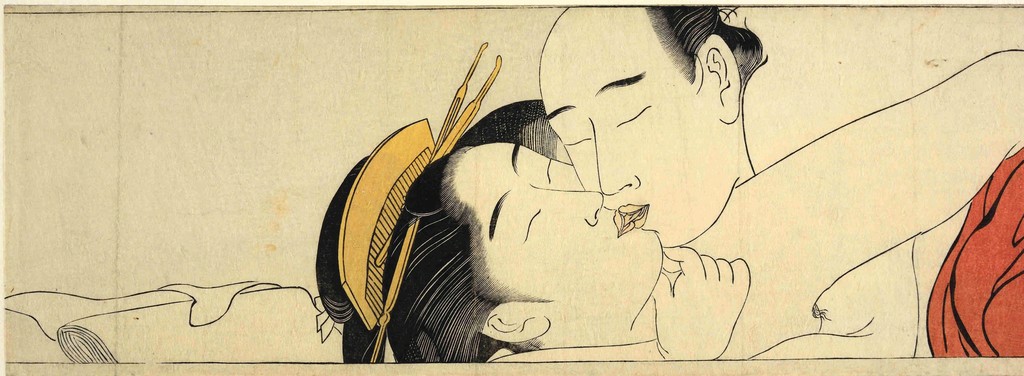

Hokusai had a long career, but he produced most of his important work after age 60. His most popular work is the ukiyo-e series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, which was created between 1826 and 1833. It actually consists of 46 prints (10 of them added after initial publication). In addition, he is responsible for the 1834 One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji (富嶽百景 Fugaku Hyakkei), a work which "is generally considered the masterpiece among his landscape picture books." His ukiyo-e transformed the art form from a style of portraiture focused on the courtesans and actors popular during the Edo period in Japan's cities into a much broader style of art that focused on landscapes, plants, and animals. Hokusai also executed erotic art, called Shunga in Japanese. Shunga was enjoyed by both men and women of all classes. Superstitions and customs surrounding shunga suggest as much; in the same way that it was considered a lucky charm against death for a samurai to carry shunga, it was considered a protection against fire in merchant warehouses and the home. From this we can deduce that samurai, chonin, and housewives all owned shunga. All three of these groups would suffer separation from the opposite sex; the samurai lived in barracks for months at a time, and conjugal separation resulted from the sankin-kōtai system and the merchants' need to travel to obtain and sell goods. Records of women obtaining shunga themselves from booklenders show that they were consumers of it. It was traditional to present a bride with ukiyo-e depicting erotic scenes from The Tale of Genji. Shunga may have served as sexual guidance for the sons and daughters of wealthy families.

Documentaries and Works

"Hokusai Returns: Japan's Greatest Ukiyo-e Artist" (1987) is a Japanese television documentary about a project undertaken in 1986 to take a collection of woodcut blocks by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and return them to Japan to make new woodblock prints from them. The collection had been donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts by William S. Bigelow (1850-1926), an American who had lived in Japan for a number of years in the 1880s. The film documents the process of making the new prints. Special attention is paid to the picture book, "Toto Shoukei Ichiran." This film should interest art history students but is of even greater value to students who plan to go into art restoration or work in museums, given the way it follows each step of the process by museum staff members in both Boston and Japan and then by the craftsmen recreating the artwork. The film is 53 minutes and was produced by the Tokyo Broadcasting System. This version is narrated in English by Nigel Robins. Given the continued popularity of Hokusai, arguably the most famous of Japanese woodcut artists, this film should be much better known.

The Lost Hokusai Documentary 2017 (UPDATED 22/7/2017)

In his last years, Hokusai painted a final masterpiece that was destroyed by fire in 1923

2017 documentary - Hokusai Old Man Crazy to Paint by BC Documentaries

In his last years, Hokusai painted a final masterpiece that was destroyed by fire in 1923

2017 documentary - Hokusai Old Man Crazy to Paint by BC Documentaries

2014 documentary about the life and work of legendary 18th/19th century Japanese painter and print-maker Katsushika Hokusai.

Hokusai died in 1849, just four years before the opening of Japanese ports to the West dramatically altered Japanese culture. See how Hokusai’s art perspicaciously hinted of things to come, including a fascination with technology, curiosity about the outside world, and growing sense of Japan as a nation.

A couple of Hokusai's notable works

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Also below the Dream of the Fisherman's Wife (蛸と海女 Tako to ama, Octopus(es) and shell diver) also known as Girl Diver and Octopuses or Diver and Two Octopuses etc the image is literally two octopi entwined sexually and ravishing the diver who appears to be enjoying herself and has become Hokusai's most famous shunga design.

It is included in Kinoe no Komatsu (English: Young Pines), a three-volume book of shunga erotica first published in 1814

Link to Hokusai Wikipedia page here